|

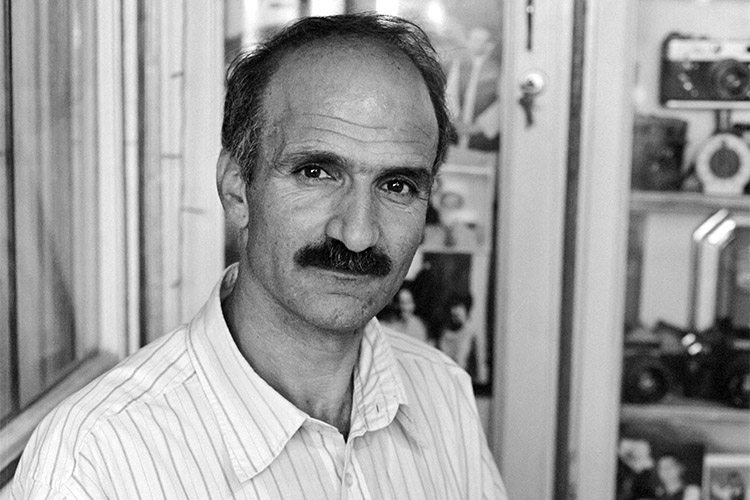

| HEKMATULLAH ARABABZADEH | |||||||

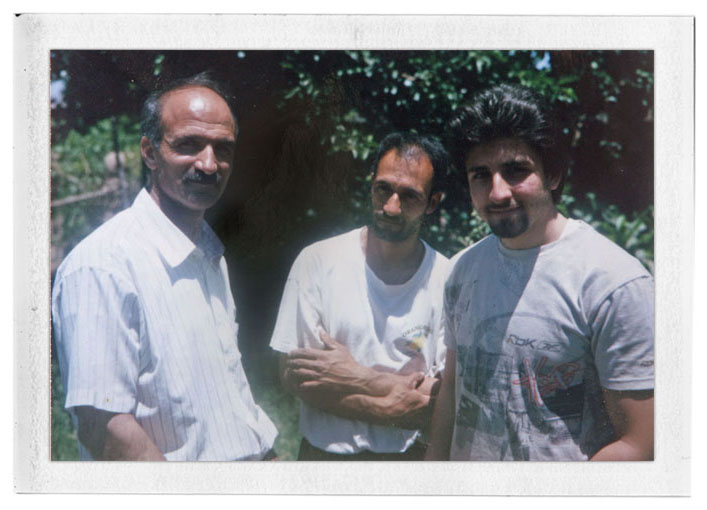

"Do you want to know why I became a photographer? I will tell you!!" We are picnicking with Hekmatullah in his family garden on the outskirts of Herat. His story begins when he was eight years old, with what his young eyes thought were "little toys" falling out of the sky over this very garden. The toys were bombs, part of a Russian aerial assault that devastated his neighbourhood and city. But Hekmatullah transforms the story into a moment of childhood wonder when one year later he had his very first photograph taken on an instant camera, a Polaroid, on the same spot just metres away. "I can do this with my own hands," he thought, amazed to see the photographer pull his photo out of the camera. It was a moment that affected him for a lifetime. Below: a polaroid snapshot we took of Hekmatullah (left), his younger brother Habibullah (centre), and his son Omid (right).

Hekmatullah's memories are saturated with photography and he passionately surrounds himself with them, collecting photo paper, equipment, lenses, cameras, and huge outdated photographic printing machines and timers. He wants to open a photo museum in his brother's house, he tells us beaming - "just for me". Here's a short clip of Hekmatullah showing us his old developing timer.

As a boy Hekmatullah started his career as a photographic printer in Mashad, Iran, a city where he and his brothers found shelter from war. It was also the city that gave him his profession, and where he started his own family. Like many Afghans he worked illegally in Iran, where he stayed for thirteen years. Working in the photo studio in Mashad, Hekmatullah had the opportunity to experiment with developing techniques, montages and different kinds of backgrounds. And he is an enthusiastic experimenter. The first outdoor (non-studio) photographs he took were after work at night, playing with the reflections and electric lights of the city when the sun went down. Eighteen years ago during Mujahedin times he returned home to Herat with a young family, and he has owned or part-owned four studios since. Over the years if he was met by economy of means he overcame it with creativity, loading his Zenith with a single cut film if he didn't have a roll, and when he needed a projector, he made one, as can be seen below.

During the Taliban times Hekmatullah used to print wedding photographs at home despite only passport photos being permitted. On one occasion he was jailed when the Taliban discovered him with a 'contraband' negative showing a man and woman of uncertain relation. "For one negative, one night in jail," Hematullah says laughing. His brother was luckier. He had a pocketful of wedding photographs on him at the same time but managed to avoid arrest. After the Taliban were ousted photography grew day by day, Hekmatullah explains, and he enthusiastically lists a whole technological evolution of cameras and lenses he bought since then, until he reaches his last analogue camera - and stops. Back in the basement shop that he rents from Maher he gets his son, Omid, to hand him a cardboard box once used to store photo paper "My treasures," he says. "Over time I have collected these." He opens the box. It is full of kamra-e-faoree negatives that he started collecting ten years ago when he realised the box camera's days were numbered. "All the photos are from one photographer," he says, "Ali Ahmad who would go around and outside of the city." He offers us some of these photographs but we are reluctant to accept another man's treasure. "Take the photos," Hekmatullah insists, "I am the donor of this project." See a gallery of Hekmatullah's box camera photo collection here.

|

|||||||